Background of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis research (part 1)

Downloads

Abstract

Annotation. This article presents the history of the finding of the maxillary sinus and the transformation of ideas about its relationship with teeth and their diseases. The researchers and some of the historical events that influenced this process have been named. The author’s descriptions are given, they illustrate the level of study and understanding in the corresponding historical periods.Key words:

maxillary sinus, history, odontogenic sinusitisFor Citation

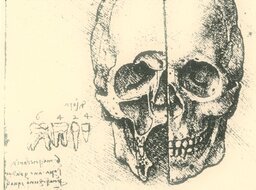

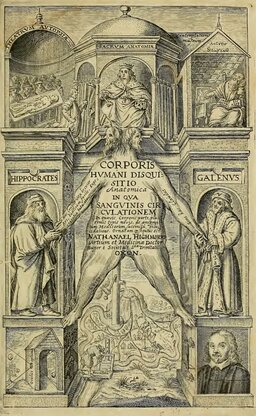

The topic of maxillary sinusitis is often discussed in medical publications. Therefore, it is somewhat paradoxical that the history of the issue is rarely brought up, not well known and underappreciated. For example, there is a strong belief that the maxillary sinus discoverer was Nathaniel Highmore, who sketched and described it in his treatise Corporis Humani Disquisitio Anatomica, published in 1651, although drawings and descriptions found in Milan in 1901 have proved that maxillary sinus was first discovered and illustrated by Leonardo Da Vinci in 1489 (Fig. 1) [1, 2].

Despite being interesting, the history of some specific issues, including the study and surgery of odontogenic sinusitis, is even less known. However, this information is necessary for professional development of otolaryngologists, dentists and maxillofacial surgeons.

The anatomical proximity of the maxillary sinus to the teeth was stressed even by the first discoverers — Leonardo da Vinci and Nathaniel Highmore. Da Vinci sketched and described the interrelations between the maxillary sinus and the teeth and speculated that the sinus “contains the vital sap that nourishes the roots of the teeth”.

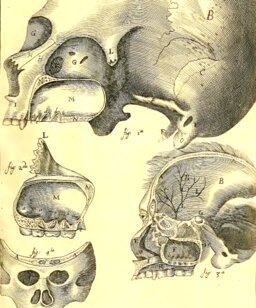

Highmore also sketched the connection between the maxillary sinus and the teeth and gave the following verbal description: “…that bone which surrounds and separates it from the alveoli of the teeth, is slightly thicker than wrapping paper. At the base of this cave one can discern some convex protrusions. They enclose the thin tips of the teeth. Into the lower edge of this bone dental alveoli are incised, in which the teeth are anchored…” (Fig. 2) [1].

It is difficult to say whether da Vinci saw the teeth as the source of the sinus diseases, but it seems clear that Highmore had no doubts about the fact as shown by the clinical case he gave as an example.

Highmore described the story of one patient, which has since been told many times in the books written by James Drake and Jonathan Wright, as well as in articles by Harald Feldmann, A.S. Seregin et al. and others [2—5].

Highmore wrote: “Here I must tell what happened to a noble lady whom I was treating. For a long time she suffered from untreated teeth decay and persistent purulent fistulas. She had almost all her decayed teeth pulled out. Nevertheless, she suffered from pain until finally her left canine was removed. However, upon removal, the squamosal bone between this maxillary cavity and the tooth pit was also removed. Consequently, from this cavity, through the pit of the aforementioned tooth constant outpouring of body fluid occurred. Frightened by this, she inserted a silver stick into the hole to understand the source of the fluid, and pushed it about 2 inches towards the eye. Frightened even further, she pushed a feather through the hole, which went even deeper. She was very frightened and thought she had reached the brain. She consulted me, I asked about the particular details, soon discovered a recurrence of inflammation and realised it was in her sinus. I showed her a picture of the sinus and explained its necessity and role. Since then she has patiently endured this constant running secretion, fear and treatment…”

We can assume that this connection was also understood by the pioneers of maxillary sinus surgery, Johann Heinrich Meibom, Theodor Zwingler, Lorenz Heister. They performed the maxillary sinus antrostomy through the alveolar socket, although it's unclear why they were removing teeth in the cause of surgery: as a source of inflammation or to get an access into the sinus cavity (Fig. 3, 4, 5) [4].

The method of maxillary sinus antrostomy through an alveolar socket is most commonly associated with the name of William Cowper, the author of the Section for Dr James Drake's Anthropologia Nova, published in 1707 (Fig. 6). The Section was devoted to the description of the sinus and to the treatment of its purulent inflammation. After reading, there is no doubt left that Cowper saw a connection between sinus inflammation and dental diseases. In particular, in the text he speaks about the thin bone separating the tooth root apex from the maxillary sinus, the bad breath from the nose, which can be cured by extracting the tooth, performing maxillary sinus antrostomy and irrigating the sinus through the alveolar socket. The text is illustrated with drawings in which the author depicted caries on the first molar and periodontitis contacting the sinus floor on the second molar (Fig. 6) [3].

As a clinical case example, Cowper outlined the story of a Highmore's patient, although he could have told the equally striking story of the great “Sun King” Louis XIV which was well known in Europe at the time. In 1685, the French King was treated for an “empyema of the maxillary sinus”. All the teeth on the right side of his upper jaw were pulled out because the teeth were in poor condition. After extraction, fistulas formed through the alveolar sockets into maxillary sinus which led to oroantral communication, so when drinking or rinsing the mouth the King had liquids pouring from his nose.

The doctors made a collegial decision to cure the fistula by cauterizing. And the King's doctor, Dubois, managed to heal it by cauterising the fistula with a red-hot instrument but only on the fifteenth attempt. After the procedure the King then began to discharge foul-smelling pus from his nose, which was very disturbing to him. The source of this discharge was already considered by doctors to be “reticular bones” (l'os cribleux) of the nasal cavity. Whether or not the King was cured from this physical affliction is unknown, but it is known that with his permission, the story was described in detail in the Journal de la Sancte du Roi and the King himself enjoyed rereading it more than once. In the article the King's Head physician, Antoine d'Aquin, wrote that the King showed more strength and fortitude than the surgeon, who by the end of the treatment was utterly exhausted [6].

We should also mention that the history of the King's illness had an impact on the development of sinus surgery. In the 1740s and 1960s at the Royal Academy of Surgery in Paris the issue of the preferred method of sinus inflammation treatment procedures was widely and vividly discussed. Louise Lamorier proposed his own method of opening the sinus from the oral anteroom, while Jourdain (Anselme Louise Bernard Brechillet Jourdain) proposed his own method of probing and irrigation through the natural opening of maxillary sinus in floor of sphenoethmoidal recess. The decision was made in favour of Lamorier's method, and although, according to the published data, Toussaint Bordenave who supported the transoral and criticised the endonasal method as 'too harsh` played a major role in the decision, Feldman believes that it was the story of King Louis XIV that influenced the decision made by Royal Academy members. As a result, the Lamorier method became the standard for the next 120 years [2, 4, 7, 8].

In 1746, Dr. Pierre Fauchard for the first time described a case of a tooth fragment that had been pushed into the maxillary sinus during extraction. Similar cases were later described by Bordenave, Heinrich Adolf von Bardeleben, Froustein and others. The doctors reported that the most common complication in such cases was the development of purulent inflammation in the sinus, but sometimes there were no adverse consequences. Froustein and Sternfeld shared clinical observations that, during the sinus irrigation or blowing the nose, the root fragments fell out of the nose and the purulent process stopped (Fig. 7) [9].

In Russia, Professor Ivan Fedorovich Busch at the St. Petersburg Medical and Surgical Academy was one of the first scientists to draw attention to odontogenic maxillary sinusitis. In his three-volume manual on surgery, published in 1807, he distinguished rhinogenic and odontogenic processes — the cause of the latter was defined as “decay in the dental pit”.

In practice he used the Cowper's method: trepanned the sinus through the dental alveolar “at the place indicated by the disease itself or optionally at the place of the second or third tooth on the affected side” (Fig. 8) [11].

The history of the XVIII and XIX centuries was not distinguished by in-depth study of the sinusitis etiology, nor by active surgery of the sinuses. Diagnostic methods were limited to complaints collection and superficial dental evaluation. Sinus surgery during this period was haphazard, limited to perforation performance for the drainage of pus, without any revision of the sinus, and certainly did not give any insight into what was going on. There was a slow accumulation of clinical observations without analysing and summarizing them.

The story of the famous otorhinolaryngologist Karl Ziem, published in 1886, can be an excellent and illustrative example. It is particularly interesting because it is not only based on his professional experience, but is also his own medical record.

Ziem wrote: “…In 1877, due to a cotton mouth pack remaining too long in the upper molar, which was decayed from tip to root, initially a runny nose and later nasal pus developed… Injections and inhalations with disinfectants and antiseptics, methodical nasal ventilation, application of medicinal powder to the nasal mucosa, internal application of arsenic, turpentine and a two-year stay in sunny Egypt was unsuccessful. The antrostomy of the right maxillary sinus through the alveolar process with a sharp spoon, which I carried out in 1881, was also unsuccessful, probably because the opening of the sinus was incomplete. In 1883, when I had to treat a sore ear, the rhinorrhea and odour from the nasal and oral cavity became so profuse and noticeable, that it was more and more frightening. I was even thinking about giving up the practice in the near future. In November 1883, in order to somehow get rid of this dreadful affliction I went to Dr. X., ready to have the antrostomy on my maxillary and other nasal sinuses if necessary. Dr. X. was reluctant to perform the surgery I desired as I had no symptoms of swelling and enlargement of the maxillary sinus. However, contrary to the doctor's expectations, after the sinus was opened with a drill through the alveolus, a large amount of liquid pus with a very strong odour discharged. In an attempt to widen the surgical opening, part of the sharp spoon used to do so broke off and stuck in the cavity. After unsuccessful attempts to extract it, Dr. X., who was probably unaware of the true size of the fragment, cursed himself and me that he had so soon agreed to perform the surgery. Unfortunately, despite several weeks of lavage, the pus did not stop in the presence of the foreign body, but a profuse secretion of saliva followed.

Appetite and sleep were severely impaired, the latter could only be induced for a few hours by drugs or large quantities of alcohol. Persistent festering, fevers, swelling of the spleen, heartbeat arrythmia and a high degree of nervous system excitement caused increasing despair and doubts about a favourable outcome. Finally, after three months, the fragment of the iron instrument had become so loose that it was easy to remove with forceps. It was about 5 mm wide and 7 mm long. Soon the festering stopped. More than a year and a half has passed since then, and there is not a fraction of the former suffering…” [12].

Occasionally, doctors reported inflammation of the sinus and accompanying findings of retained or dystopian teeth, protruded tooth fragments etc. Without categorizing and systematization these stories sounded casuistic, but their number was growing and sinus diseases were increasingly associated with dental and jaw diseases.

To be continued…

References

- Highmore N. Corporis humani disquisitio anatomica. — The Hague: Samuel Brown, 1651.

- Feldmann H. Die Kieferhöhle und ihre Erkrankungen in der Geschichte der Rhinologie. — Laryngorhinootologie. — 1998; 77 (10): 587—95. DOI: 10.1055/s-2007-997031.

- Drake J. Anthropologia nova. — 1717.

- Wright J. A History of laryngology and rhinology. — Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1914.

- Серегин А.С., Супильников А.А., Тарасов Ю.В. Эволюция представлений о верхнечелюстном синусе. — Вестник медицинского института «Реавиз»: реабилитация, врач и здоровье. — 2019; 4 (40): 38—44. eLIBRARY ID: 41333997.

- Vallot A., d`Aquin A., Fagon G.-C. Journal de la santé du roi Louis XIV de l‘année 1647 à l‘année 1711. — Paris, 1862. — 482 p. https://gallica.bnf.fr

- Barbaix M., Clotuche J., De Jonckere P., Halleux R., Hamoir M., Hennebert P., Jeannerod M., Klotz P., Michel J., Micheli-Pellegrini V., Minet J., Opsomer C., Pirsig W., Rodegra H., Rysenaer L., Segal A., Simon I., Stephens S., Sultan A., Eeckhaut J.V., Verriest G., Verstraeten P., Willemot J. Naissance et développement de l‘Oto-rhino-laryngologie dans l‘histoire de la médecine. — Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. — 1981; 35 Suppl 2: 1—392. PMID: 7025562.

- Mion M., Zanon A., Marchese-Ragona R. The history of paranasal sinus surgery. — Medicina Historica. — 2017; 1(3): 139—46.

- Kolibay. О связи между зубными и носовыми болезнями. XII Одонтологическое обозрение. под редакцией И.М.Коварского. — 1910; 1: 1—9.

- Kolibay. О связи между зубными и носовыми болезнями. — Одонтологическое обозрение. — 1910; 2: 71—8.

- Буш И.Ф. Руководство къ преподаванiю хирургiи. Ч. 3. — СПб.: Императорский Воспитательный дом,1823. — 727 с.

- Ziem K. Ueber die Bedeutung und Behandlung der Naseneiterungen. — Mschr Ohrenheilk. — 1886; 20: 33—43, 79—84, 137—147.